Episode 7: Kenneth Josephson and Marilyn Zimmerwoman

In this episode, renowned photographers Kenneth Josephson and Marilyn Zimmerwoman are in conversation with Museum of Contemporary Photography’s curator of academic programs and collections, Kristin Taylor. The artists discuss several works made over Josephson’s decades-long career as well as topics ranging from composition and perspective to the male gaze and Marilyn Monroe.

Chicago Josephson, Ken 1964

Matthew Josephson, Ken 1965

Chicago Josephson, Ken 1973

Chicago Josephson, Ken 2009

MZ Josephson, Ken 2008

Interview Transcript

Kristin Taylor:

This is Focal Point, the podcast where we discuss the, artists, themes, and processes that define and sometimes disrupt the world of contemporary photography. I'm Kristin Taylor, Curator of Academic Programs and Collections, with guest Kenneth Josephson and Marilyn Zimmerwoman. Kenneth Josephson is one of the first artists to work with photography conceptually. He began making pictures about photography itself in the 1960s. At that time, the medium was just becoming accepted as an art form worthy of exhibiting and collecting. Josephson was one of the few artists willing to think critically about the limitations of the camera. Many of his images playfully push the boundaries of the viewfinder and the borders of a print, often placing photographs within photographs or showing his own hand within the frame. He lives in Chicago with his camera in tow, where he continues to make gelatin silver prints in his own dark room.

Kristin Taylor:

Marilyn Zimmerwoman is an artist and educator who's dedicated to teaching where the arts and social justice intersect. She is currently an artist-in-residence at the Center for Peace and Conflict Studies at Wayne State University in Detroit, where she also taught photography for 40 years. Her work centers on issues of gender, race, class, and economic disparities and pushes her people to become citizen artists, participating in global actions around justice. she often collaborates with their partner Ken to create images that playfully pushed expectations of a photographic portrait.

Kristin Taylor:

Ken and Marilyn are both artists included in that museum's permanent collection. And normally, we discuss a work they have each chosen from the museum's collection, but to help stop the spread of COVID-19 we are recording the session over Zoom and not in person. So, they'll be talking about several works that they have in their home that have been made by Josephson over his multi-decade career. These images will be posted to the museum's website at mocp.org/focalpoint so you can always go and see them there. Also, because we're recording over Zoom, the quality of this sound might not be as good as if we normally record in the WCRX FM radio station.

Kristin Taylor:

Well, welcome and thank you for joining us today. I was looking up to meet both of you a few times before now, and we talked a lot about the normal questions that I think you get about conceptual photography and your immense background in photography. But, I wanted this conversation to be a little bit more relaxed and to focus on your collaboration together and how you're fairing right now as image makers in this time of social isolation because it's just a very unique time to be speaking with one another. so, hopefully, we touch upon some of the things in your background that everyone, I'm sure, wants to know about with you studying at Institute of Design and how you arrived at conceptual photography. But, my questions are going to be a little bit more about your collaboration, and your relationship, and your partnership as artists.

Kristin Taylor:

To start, I hoped you guys could talk about the pieces you chose because normally, we meet in the museum's vault, and we look at prints together that are in the museum's collection. But since we're separated, you have a print now that I hope you can describe verbally to people since if they're not looking at it and they're just listening to headphones so they can imagine it. what it looks like and what stood out to you about this image of all the images you've made or that you have in your home right now why you chose to talk about this one?

Kenneth Josephson:

All right. First of all, I feel like I'm maybe trapped in a Mr. Roger's Neighborhood episode because this is coming from my living room, and I'm casually dressed. Anyhow, boys and girls, this particular image I made in 1964, and basically, I wanted to create a sequence of images that would end up within one image, rather than stringing out from left to right three images or four images. As you can see, I photographed Polaroid the image from a distance, so it is a short journey as I moved toward this tree. Then, I placed the first image onto the bark of the tree and made a second image on Polaroid, and then place that to the bark for the final 2 1/4 inch film image.

Kenneth Josephson:

And I thought that as a contained sequence was more interesting than stringing them out. And I think I was probably influenced by some of the work of Edgerton, perhaps, who did a lot of motion studies of athletes, and which the sequential time was recorded within one image through electronic flash. So I think Marilyn wants to add...

Marilyn Zimmerwoman:

I think, then, when you talk about your logic class and how that led you to be the most expedient about how to get somewhere in the most direct way, informed your decision to, "How can I make a sequence within one image?" And that expediency of kind of a Swedish sense of design and aesthetic, also. And you have a clarity in your thinking that it is essentialized often. And you can just cut through in one sentence a very perceptive description of what's going on of what we're seeing of everywhere.

Marilyn Zimmerwoman:

And what I find about your way of articulation is that it's been very inspiring for students who may be less verbal or more quiet to see how you can have such an expediency of words in a moment where we're have such a hyper theoretical framework. But in your expedience, you have words, it also speaks to your expediency of composition and the accessibility through formalism. So clarifying the theory that has evolved to become such a mega theory and kind of about hyper articulation that MFA programs have become.

Kenneth Josephson:

It's a way of being very economical, is the way way I kind of think about it.

Marilyn Zimmerwoman:

There's a saying about writing, that writing should be so essential so that every word is gold. And when you're writing, if you have to make a short essay, you need longer to write it because it has to be so clear that every word is structural to that meaning.

Kenneth Josephson:

There's a study made to find out the very basic use of objects. And one study was the use of a pencil, and pencils were given to a group of children, and they were asked what they were made for using. And people would say "draw" or "write words." And then, finally, one person said, "To make marks." And that's very basic thing about the use of a pencil, they can make holes and things, but it makes the best use of it is making marks of some sort. And I always admired that kind of way of getting down to the very pure use of something, or have an idea, or whatever. And I always had that in mind.

Kristin Taylor:

Have you ever tried other mediums? Because when I look at this image that you have up right now, I think of music, and I think of the notes repeating. And I studied painting in my background, and I've never tried to be limited to the camera because I find it frustrating that you can only do so much. Of course, you can do so much more. You have to be very inventive and creative like yourself. But with your interest in rhythm and repetition, have you ever tried other materials? Or has it always been about the camera?

Kenneth Josephson:

Only use of found objects, some sculptural ideas. I'm very fond of music. I listened to it a great deal, and I enjoy it very much. I'm sure it's influenced my work in some way. I'm not sure exactly how, but maybe you observing can understand, maybe, some kind of connection more than I would.

Marilyn Zimmerwoman:

I think the limitation of the frame is helpful because the limitation is what helps to have such a clarity of composition so the creation couldn't go deeper within that limitation of the framing. Because, in my undergraduate degree in painting, I never knew when a painting was done. But somehow, there was more of an aesthetic click in a photograph. And that was made so much more clear in the process and so, that's what made me choose photography. And there's a sense that Ken and I both read a lot, and Ken read a lot as a boy. And you talk about his excitement going into a library.

Marilyn Zimmerwoman:

So we're both readers. Our time here is spent during this moment of being confined in our space together. This quarantine is that our days are like a library. And we're very quiet, and that we're going into our interiority, and there's big expanses of silence. And two hours of silence, by the way, builds brain cells. But, it also is a sense of a deepening of that own dialogue. And I think that sense of questioning, and that sense of excitement, and that sense of going deeper, is what was mind for both of us in our sense of our reading, and our solitude, and a strong sense of self-reliance and agency.

Marilyn Zimmerwoman:

And this was made by Ken in a time when that kind of reference of the photograph was being displaced from being the equivalence of the landscape and a sense of an experiential reality equivalent to the vastness of the mountains or truth itself. And forensics, that interruption of the frame or that the image about the image making it self-referential was made at a time where it was violating the previous rules.

Marilyn Zimmerwoman:

So it was a violation, and that introduction of the hand was a violation, and he felt a gut response. But as this photograph was made at Chicago in 1964, it's an image of a tree within the tree closer, within an image of a tree closer. And so, it speaks to the recursive patterning of representation, which speaks to fractals, and fractals was first used by mathematician Benoit Mandelbrot in 1975. So, this was made before fractal was named and brought to the public awareness. But it's so about that. And so, that's interesting about, has artists intuitively absorb in this kind of collective consciousness? What's evolving? Because we are a verb. We are a verb. We also are evolving with it. So I find that for this photograph representing that, and a fractal is a never ending pattern, they're self-referential. They're created being a repeating of a simple process over and over in an ongoing feedback loop.

Marilyn Zimmerwoman:

And so, Ken's images speak to that clearly with an accessibility of formalism and a sense of clarity. So fractals are a sense of an infrastructure all around us. They're modeling structures from eroding coastlines to snowflakes. And examples include clouds, snowflakes, mountains, river networks, cauliflower, broccoli, our systems of our own blood vessels. And then, they're in the physical realm limited by space and form, but they're also, in theory, fractals repeat to infinity. And so, this is a duality in terms of an object that's a flat image, and it speaks to the flat image of the photograph, but it also speaks to that sense of fractals being that infinity of experience. That the trees represent in terms of their own mimicking of the blood vessels, from the top of the tree equal to the bottom of the root system.

Marilyn Zimmerwoman:

And that they're systems that reflect how we are created. So, it's like fractals speak to the holographic universe. That what's in the one is in the whole, and the systems of the tree are related to our inner system. And so, as fractals relate to a sense of the holographic universe, it also speaks to that sense of in the reference to the photograph, what's in the one is in the whole to our sense of being human. So this is interesting about what we make as images are also where we're at in terms of this being human. And the idea of a holograph, what's one in the whole, is like what Rumi said when he wrote to us. Rumi's a 13th century Islamic poet, mystic lover of humanity. And he wrote, "You are not a drop in the ocean. You are the entire ocean in a drop."

Kristin Taylor:

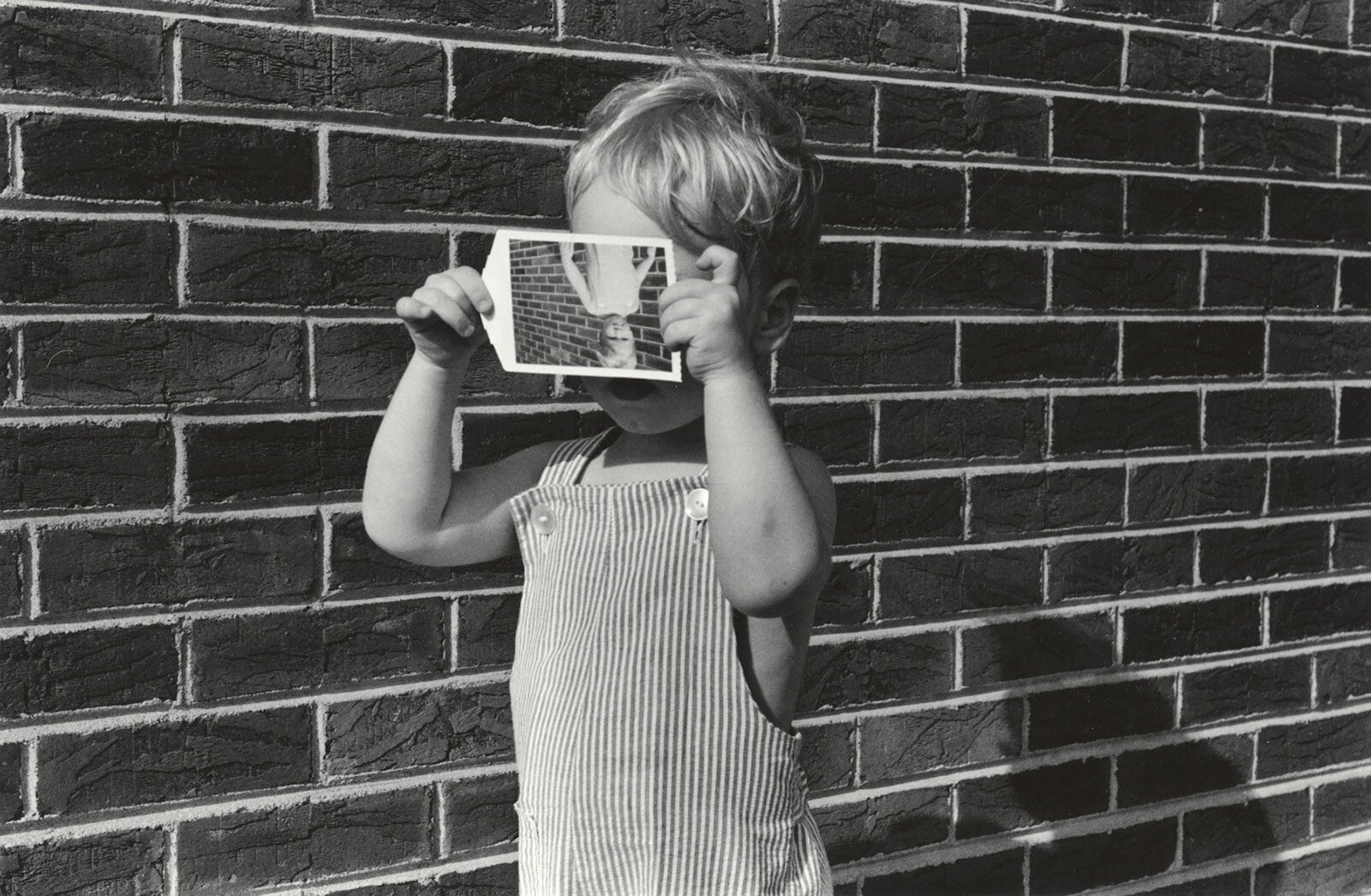

That's great. And I love that you chose this example to talk about your work. And then, the other that I understand you're going to talk about is of your son holding a photograph. And thinking about a lot of things you both were just saying, I feel like that image now has new meaning for me too, about family and this idea of your children being part of your own fractal. I've never thought of parenthood in that way. But, is that something you were thinking about when making that image? Or should we switch to that one and talk about it a little bit?

Kenneth Josephson:

This image of my son, Matthew, he was two years old at the time. And I was out with him making some Polaroid images. And I also had my 35mm camera with Marilyn. I was showing him the images. He would pick them up and look at them. And then, he suddenly put that one up to his face, so I made a 35mm image of him doing that. And he was mimicking the way I was holding the camera, with his finger on what would be the shutter release. Because the image on the paper is translucent, he could see through it. Of course, not when it was right up to his face, but I think he was making an image with the camera or using the image as a camera. So it came together, I thought. Unexpectedly, I didn't plan this out or anything. It just happened. Happily, I was able to record that. It speaks to the child's curiosity and playfulness, all the things that little children are made. Also, there's this image.

Kristin Taylor:

I love it. This is the one you told me about yesterday when we talk. So in case anyone's listening only on radio, we need to describe this one visually.

Marilyn Zimmerwoman:

Would you like to describe it?

Kristin Taylor:

Sure. Yeah. So we see, just from the neck down, a woman's shirt and her cleavage is poking out with four photo corners attached to her body around the cleavage framing. It great, I love it. I've never seen this one, but you told me about it earlier. So did you make this just recently or tell us about it?

Marilyn Zimmerwoman:

Well, this is more a while ago that the one that we...

Kenneth Josephson:

This is 2008. The last one was more recent.

Marilyn Zimmerwoman:

Last year.

Kenneth Josephson:

Last year, yeah.

Marilyn Zimmerwoman:

So we've been together 13 years, but we've been friends. We met at the Art Institute, so we've known each other since 1976. So we stayed friends all this time. It's really good to be friends for decades before you become partners [crosstalk 00:19:43] everybody's life.

Kristin Taylor:

Especially right now, as we're all stuck in doors with one another. This reminds me, though, of an older piece that you made that we have in our collection where it's more just on her underwear region. I don't know how to describe it so much, but like you have a photograph on top of a woman's body where she's clothed and then nude in the photograph laying on top of her body.

Marilyn Zimmerwoman:

Isn't that the Sally one with the Polaroid looking through her clothes?

Kristin Taylor:

Yeah, I can't remember the title.

Marilyn Zimmerwoman:

[crosstalk 00:20:21] shot of her bush over her miniskirt, and that's one of his biggest sale items. Everybody wants that one because it's actually looking through one's clothing, like how men unconsciously dress women, or there's just that. And so, when Ken got corrective lens surgery, wasn't it? And Ken's very modest, so I'm all about letting them know who he is as a photographer and look at his images, and this is who he is. Everybody loves the image of Sally with her miniskirt and then the Polaroid. So when we came back to get the overview of how successful the operation was, Ken thanked the surgeon for also conducting the surgery so that he could now see through women's clothing, like he always wanted to. And the doctor was right there on the joke and said, "I'm glad you are giving me that gratitude, but keep it a secret."`

Kristin Taylor:

You were knocking down his door. That's what I love about this photograph, and the other one that we were just talking about, is you're, sort of calling out, I think, a very common pattern with male photographers photographing women, and maybe using the camera as an excuse to get them undressed for the camera. So, I love that [sly 00:21:50] humor, again, but it's also a sort of dark humor because we know how real these types of photographs are, and we've seen them so much. I love it, it's great. And Marilyn, it seems like you're kind of prompting the joke forward and being a very willing model, which I love.

Marilyn Zimmerwoman:

Yeah. I love it also because it's the male gaze, but it's double coded because there's the reference to the body, the figural form, which men are so enamored by. And then, with the photo corners, right? Like the snapshot that is so the sense of in family albums, and everybody's images of their family, and that context of the everyday use of the camera. So it collapses that and makes it a photograph about photography, about the history of photography, not only in terms of how it's used in that large social sphere but also about that in terms of the larger look at the progressive art forms when minimalism was so much a part of art for art's sake. And to such a degree that it blew people away because that was a huge shift for a lot of artists that were working so representationally.

Kenneth Josephson:

Yeah and this isn't Polaroid. I'm not sure if Dr. Land really intended this, but it was very useful for pornography because you could bypass the process in houses.

Kristin Taylor:

Yeah, you're, you're not having another set of eyes on the things you're making. Yeah, that's so interesting.

Kenneth Josephson:

Processing houses used to confiscate pornography.

Marilyn Zimmerwoman:

And people at camera stores used to talk about happy couples behind the SX-70, and he knew what their intent was.

Kristin Taylor:

When you're photographing together, how do you work out your two personality types? If Marilyn's more of an extrovert, and Ken, your more of the introvert, and you're both artists, and you're making images together, is there a long negotiation process, or is it pretty natural?

Kenneth Josephson:

That seems to be pretty natural, pretty much flows. Marilyn will come up with an idea, especially through her clothing, and I'll have an idea of how the image should be posed. and we work together on it usually.

Marilyn Zimmerwoman:

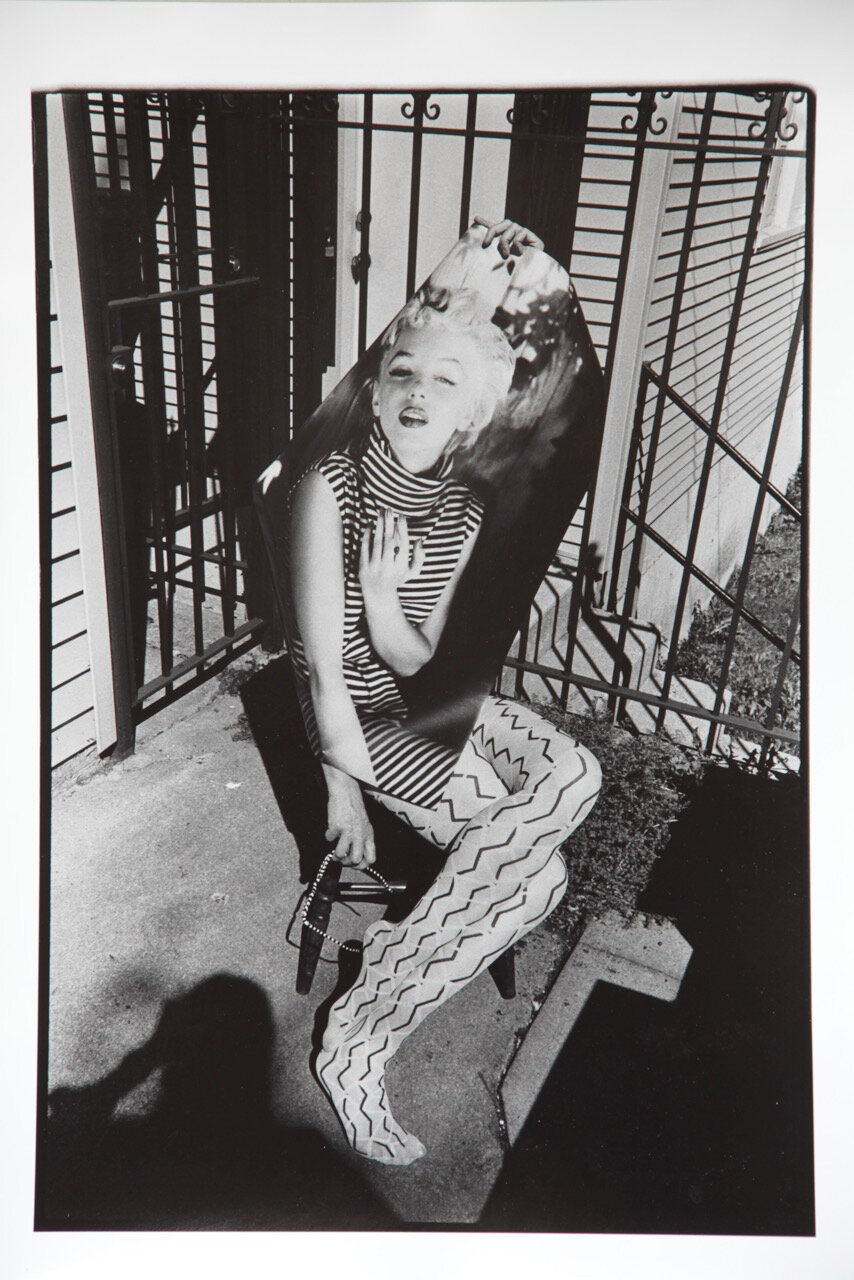

Actually, Jennifer Norback put this together. The gallery owner, Jennifer Norback. At her gallery we had a show, and it was about the photographs that we collaborated on and then the sense of referencing Marilyn. So, as Ken makes photographs about photographs, he was meta before meta was meta, as Chris Borrelli coined when he wrote about him. So I'm like meta-Marilyn.

Marilyn Zimmerwoman:

My dad said that he named us all after movie stars, and I have an older brother named John Wayne Zimmerman. And when Marilyn Monroe committed suicide, I was nine and all day, I was teased. I was a majorette. I went to majorette practice, and all of the little girls, when I came to practice, they all ran away saying, "She's a ghost. She's a ghost." So, everybody was projecting Marilyn onto me. So my peer group was, and then, I came home, and my dad, who adored me and was a workaholic, alcoholic is every 1960s, white collar worker was, largely. Wild boy trying to be in that sense of that constrictive workforce to a wild man and a wild boy inside. So he greeted me. And then, first words he said was, "Don't you ever do what she did. Don't you ever give up. You're just like her. You're just like her. You're beautiful. You're talented. Don't you ever, ever give up."

Marilyn Zimmerwoman:

And Marilyn, the iconic Marilyn, is the one that we all love because she was vulnerable, because she was also a lot of fun, because she brought humor and her vulnerability into sexuality. And so, that sense of child-likeness hooked all of us in terms of us all feeling our own insecurities and vulnerability. But that's also where you're most authentic.

Marilyn Zimmerwoman:

So, that's that sense of why she's been so enduring, but that sense of I feel like I carry her hope consciously, in terms of owning that download culturally because all of us, energetically, my peer group was the "me" generation that was the first to download the television our own sense of our own peer group, of music, and the media, and then, increasingly media's so influential to us in terms of who we are as a human being. That energy. And then, we're evolving with this so that we have inherited family. So this my inherited sense of identity that I had to incorporate. And I could own it, and work with it, and move it beyond, and carry her with me into my own evolution of being a radical, [anti-sedition 00:27:53] feminist. We all have different paths. But, this was another photograph. This was bigger.

Kristin Taylor:

Yeah. And I've seen this one online. I love it. It really reminds me of this artist, Natalie Krick. I don't know if you've seen her work, but I'll send you her link. It's fantastic. She plays a lot with photographing her mother and herself and...

Marilyn Zimmerwoman:

Yes. And so, this is another one that I go, "here I am." This is our backyard, and it was all of that. And I placed myself there, and I have my sunglasses that have that pattern. and there's Ken's shadow. So there's a sense that because we both...

Kenneth Josephson:

The stalker.

Kristin Taylor:

It's always the shadow going in the [crosstalk 00:28:43].

Marilyn Zimmerwoman:

We can just confluence and find that third way so easily. It's always about humor and fun, and that sense of visual pleasure and celebration of our pure delight in each other. And then loving the same things, loving photography, and loving the same sense of aesthetic click. There is a very harmonious sense of being together. And I also invest a lot in wildly patterned pantyhose. I do create a wardrobe in order to be out there in the world in a performative way. And my extroversion, wow, we balance each other because Ken is very clear about his boundaries, and in the best sense of the male entitlement. But he's like, "No, I'm not going there." Every beautiful woman has had her boundaries invaded because there's something about that culturally, that men think of beautiful woman is theirs too.

Kenneth Josephson:

Okay, what else?

Kristin Taylor:

There's one picture we have in our collection too, of Chicago, of the lakefront, where you've woven sea prints and gelatin silver prints, and playing with our perceptions of color and black and white. Can you tell us a little bit about that picture and your thoughts on color? Since mostly, it seems like you photograph in black and white.

Kenneth Josephson:

Which image is that?

Kristin Taylor:

There's one, it's of the Chicago lakefront and the skylines in the background. It's woven black and white, and color.

Kenneth Josephson:

Postcard images.

Kristin Taylor:

Right.

Kenneth Josephson:

I wanted to show the architectural changes in the city, but also to show the difference between color photography and black and white photography. A different set of information is given, whether it's black and white or color. And black and white is pretty much confined to total values, where color is mainly concerned with the color of the objects and the color of the light. I just wanted to show differences in two mediums.

Kristin Taylor:

We talk about it with students a lot when we're talking about color theory that... Oh, no, this is another... I love this one. I can send it to you. It's like horizontal strips, yeah.

Kristin Taylor:

But thinking too about the ideas of photographic truth, your work is always so great to talk with students about that. Of all the different ways you could tell a story and the choices that artist makes and even just size or color, these things that seem so basic or not interesting. Then you talk about just all the different ways. Then the person reads that image after you've made that choice and how it changes their idea of what that moment was. It's interesting to me too, because you don't have a lot of color work. Not necessarily a critique, but sort of declaring a preference that you want to stay in black and white.

Marilyn Zimmerwoman:

We just discovered that he's colorblind to a degree. All of us may have different nuances of perceiving color. It was when we were painting a fence, and I can match color, but I let him make the decision so that when he painted it, I thought it would be obvious, but it wasn't. But then, I read about colorblindness. And in some colorblindness, you see pattern more than other people. So in a way, in terms of perceiving in black and white, he has a unique perception of that through his colorblindness.

Kristin Taylor:

But you never knew it until just recently?

Kenneth Josephson:

I don't think it's severe. But for certain colors, I don't interpret correctly.

Marilyn Zimmerwoman:

That's like the challenge of having hypervigilant partners that we have in each other, you're made more aware and alert, and you discover things about you. And women have more connective tissue between the right and left hemisphere, so we tap more areas of our brain when we talk and speak, and that's why we can recover better from strokes. But I find that no matter where I go in my interiority, and I speak from it, that Ken's always there.

Kristin Taylor:

It's beautiful. I think we're getting close to being out of time for the regular podcast. But, you guys have sort of answered this, has the pandemic changed the way you've been making? Or have you been trying to photograph through this together in your home?

Kenneth Josephson:

It's okay. We are very interesting lighting that changes depending on the weather. And I augment it sometimes with artificial light. But we've been able to photograph. Especially Marilyn, during this time.

Kristin Taylor:

Well, I've loved talking with you. I'm sure you probably want to get on with your day. Okay. Well, have a good rest of your day and thank you again.

Marilyn Zimmerwoman:

Yeah. We look forward to meeting your family sometime to learn more about [crosstalk 00:34:57].

Kristin Taylor:

Definitely. Okay. All right, bye.

Kenneth Josephson:

Bye-bye.

Marilyn Zimmerwoman:

Bye-bye.

Kristin Taylor:

Thank you for listening to Focal Point. Focal Point is presented by the Museum of Contemporary Photography at Columbia College, Chicago in partnership with WCRX FM radio. Thanks to Matt Cunningham, Wesley Reno, Sam White, and Zach Cunning. Music is by [Zabey 00:35:19]. To see the images we discussed today, please visit mocp.org/focalpoint. You can also follow the Museum of Contemporary Photography on Facebook and Instagram @ MOCPCHI, that's M-OC-P-C-H-I, and on Twitter at MOCP_Chicago. If you enjoyed our show, please be sure to rate, review, and subscribe to Focal Point anywhere you get your podcasts.