Episode 2: Lisa Lindvay and Natalie Krick

In this episode, photographers Natalie Krick and Lisa Lindvay join Karen Irvine, MoCP's chief curator and deputy director, to discuss works by Andy Warhol and Kathe Kowalski in the permanent collection of the Museum of Contemporary Photography at Columbia College Chicago. In the process, the two artists also discuss their own work and themes of photographing family, intimacy, and vulnerability.

Works discussed in the podcast:

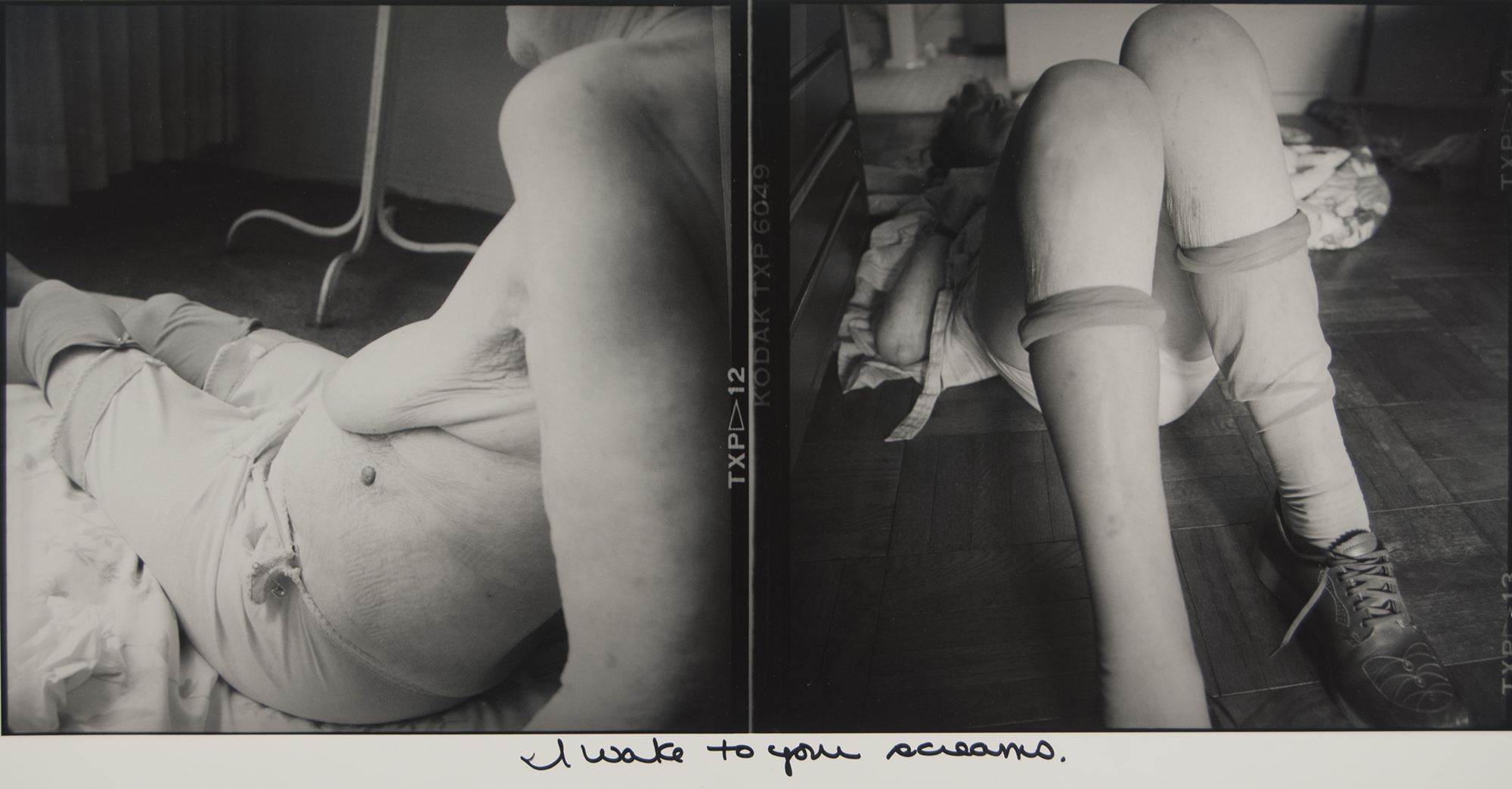

Kathe Kowalski (American, 1945-2006)

I Wake, from the "Get me some pills" series, 1991

Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987)

Unidentified Woman (short brown hair cropped top), 1985

Glamour Shots of Lisa Lindvay and Natalie Krick, 1999

Interview Transcript

Karen Irvine:

This is Focal Point, the podcast where we discuss the artists, themes and processes that define and sometimes disrupt the world of contemporary photography. I'm Karen Irvine, chief curator and deputy director here with special guests, Lisa Lindvay and Natalie Krick. Lisa and Natalie are both artists included in our permanent collection who work with their family members to create photographs that push against some of the mythology of the family and reveal some rather fraught aspects of intimacy.

In Lisa's case, she's exploring her family's existence in the wake of her mother's mental illness. Although we never see her mother, the disheveled appearances of her father, sister and two brothers is mirrored in the unkempt and chaotic appearance of their home. In Natalie's case, she explored sexuality, aging and womanhood using her mother, grandparents, sister, and herself as models, mirroring poses, and facial expressions that are seen in fashion magazines and advertisements, while at the same time revealing all of her models imperfections.

Today, we are discussing a work that they've each chosen from the MOCP's permanent collection of over 15,000 objects, as well as their own work and practice. We're standing in the vault of the museum of contemporary photography. It's a tightly packed space with high ceilings and tall shelving containing hundreds of black print boxes containing thousands of photographs, as well as movable screens that have dozens of large-scale framed photographs hung on them in all different shapes and sizes.

Lisa Lindvay:

I'm Lisa Lindvay. And I am going to be talking today about the artwork of Kathe Kowalski. They have actually pulled out two photographs from the vault for me from her series Get Me Some Pills. So the first photograph that I'm going to explain is a vertical image that is a silver gelatin black and white print. At the bottom of the two photographs, there's a sentence that reads, "She was angry at me for treating her like a child." And then the images themselves, the top image is of a elderly woman's torso. Her head's cropped out of the image.

And so really the focus is on her breasts. Because of the shallow depth of field. Her spider veins become really delicate, beautiful, curvy lines on her body. And then the image underneath her is a closeup of her knee. The knee is actually out of focus and the focus sits on her hands, which really shows you the veins and all of their detail and then scattered on the floor is a tissue, as well as if you look really closely towards the bottom of the image on her leg, you can see that there is a tube going into what looks like a bag that is either for medicine or something that's going into her at that point.

I'm going to talk about the second image, which is a horizontal also black and white. The sentence below it reads, "I wake to your screams." You can see her pants are fastened with a safety pin. It looks as though maybe she's lost a lot of weight. Her breasts sits on top of her stomach and you can see all the creases it.

And then in the background, there is a form that looks like the bottom of a coat rack that so beautifully mimics the shape of her body. And then to the right of that image is a closeup of the woman lying down on the ground. Her knees are in the foreground. Her stockings are pulled down slightly over her knees and you can start to see the slight wrinkles of the stocking, which mimic the wrinkles in her leg. In this image, it's really hard to tell if she had fallen or is laying on the ground. And it makes you kind of wonder how she got there.

Natalie Krick:

I'm Natalie Krick. And I chose a group of 20 Polaroids by Andy Warhol. They don't really have a title, but they are identified as unidentified woman, short brown hair, cropped top. There's 20 of these Polaroids. The pictures are of the same woman and a variety of different various similar poses. I chose these pictures because at first they look like flash photographs and they are flash photographs.

The light is really harsh on her skin, but then as you look closer at many of them, you can see this little area on her chest where her natural skin color shows through. Then I began to realize that this woman is actually, she had been painted white for the photo shoot.

This woman is ambiguous in many ways, mostly because a lot of Andy Warhol photographs are of celebrities. And this is this unidentified woman. It's really hard to tell how old she is because of the white makeup and the flash photography. She could be anywhere from 35 to even perhaps 55. She's smiling in most of the pictures and the smiles kind of vary from something that seems very genuine to something that's, I don't know, a little bit awkward, a little bit of a grimace.

Karen Irvine:

Thanks for being here. I have known you both for a while. Lisa, you graduated in 2009 from Columbia College's MFA photography program and Natalie in 2012. It's wonderful to have some of your work in the collection and to have watched you both kind of develop your careers as artists. I'd like to have you both tell us why you chose the images you chose. And Lisa, maybe we can start with you. I also know that you've had a personal connection to Kathe Kowalski, the artist that you chose. So in addition to talking about why you chose those images to discuss this morning, we'd also love to hear about your relationship with Kathe.

Lisa Lindvay:

Yeah. Thank you. So I chose the work of Kathe Kowalski, who is a woman that I have deeply admired and really who I think because of her I am the photographer that I am today. And so Kathe Kowalski was my undergrad professor and in a lot of ways she taught me everything that I know about photography and also really kind of shaped who I am as an artist.

And so her work, she spent many years really invested in looking at her community and as a woman really thinking about what it means to be a woman through looking at the lives of other women. And so for most of her life, she was a strict documentary photographer, which is where I think I learned everything about my formalist self, but also she had such a deep, beautiful connection with her subjects, which is what I most admired about her work.

And I think through her, I learned that by digging inward, you could really talk about kind of larger issues that were happening. And also I think really dug deep into that idea that the personal is indeed political. And so I just admired her vulnerability with her subjects, the fact that she would expose things about her own life and her mother's life that were things that I think we often look away from. And she was never afraid of that.

And so I think a lot of that really shaped who I am today and gave me the courage to really think about how I exist in the world and how that relates to other people's existence.

Karen Irvine:

And the photographs depict her mother, correct?

Lisa Lindvay:

Yes.

Karen Irvine:

Who was very ill at the time and at the end of her lifetime.

Lisa Lindvay:

Yeah. So she's worked on several different projects, but the images that I selected from the collection are of her elderly mother who was suffering from dementia. And also, I think oftentimes when we think about those kinds of photographs or we look at images of people who are aging and growing old to really talk about kind of the mental state that her mother was in, she included text.

And so the pictures are these kind of formal studies of the body, which is also a body that I think as a woman, we are ashamed of and don't often look at. Her mother it looks like she's probably in her seventies, eighties is naked in the photographs. And so there's just that sense of vulnerability to the body in itself, but also the fact that it's hard to picture a mental state. And so how do you start to dissect that?

And I think that's really where the text comes in. And so Kathe is interested in documenting the body as it is, but to really start to think about how does the body tell a story and how can language start to add to that conversation?

Karen Irvine:

Your work is similar in that it attempts to describe somebody's mental state, but of course you don't put that person into the photographs, but I would say what you have in common with Kowalski's work is just that kind of raw exposed vulnerability that you both include about own personal lives. So that seems to be a great source of inspiration for you.

Lisa Lindvay:

Oh yeah. Absolutely. I think in undergrad, I did the thing that you do when you enter photo school. And I photographed all the decay and black and white photography has this amazing ability to make things that are not so beautiful be really beautiful. And so I think once I had her as a teacher and just saw the way that she photographed people, that's where I fell in love with the idea of photographing people.

And at one point I started to photograph my grandparents and wanted to really mimic that idea. And then I stepped away from that for a little bit. Kathe actually was diagnosed with cancer while I was in school. And so that was a really hard point I think for me and my peers who admired her so deeply. And so as she transitioned out of the school to take care of herself, we had other teachers coming in.

And so that's where I started to play around with the four by five camera. And that was the time of Philip-Lorca DiCorcia and Jeff Wall and Gregory Crewdson. And this element of artifice really came into picture making. And so I feel like I wanted to hold on to my inner Kathe Kuwalski and mix those two ways of picture making.

And also just I think it gave me a lot of strength to realize that this thing was happening in my life that I didn't quite know how to deal with. And I was really able to use photography as a tool to try to make sense of that. And then through doing that, I was able to connect with other people on this kind of deeper level, because I think the things that she's looking at dealing with mental health and the things that I'm interested in are things that are really, really prevalent that we, as a culture just don't want to look at or talk about. And so it was really important for me to start to think about ways to talk about these things in a larger scope.

Karen Irvine:

Awesome. Natalie, let's hear from you about your choice of the Warhols and why you chose those and how they relate to your practice.

Natalie Krick:

Well, I'm really interested, I've always been really attracted to Warhols Polaroids and his films. And I think that they weren't really displayed during his lifetime. The Polaroids are mostly sketches for his paintings. The reason why I chose the collection of images that I did because the woman in the pictures is unidentified and most of his Polaroids are of celebrities.

And it's very, I guess, mysterious. I like to look at photographs where I don't really know the backstory and I can spend some time kind of guessing what the situation was. I guess whenever I'm looking at portraiture, I'm always kind of thinking about this dynamic that Roland Barthes talks about in Camera Lucida, which is kind of what I like to refer to as a love triangle between the photographer and the subject and then the audience. So in this case, the photographer is Andy Warhol photographing this woman who, as I said before, you can't even really tell what her age is.

We don't know who she is. Here she is wearing this tube top painted white. It's just a very kind of strange scene, not knowing the backstory. And then the audience is me. So what I've kind of concluded is she was probably an art collector. So a very wealthy woman, commissioning Warhol to make a silk screen painting of herself, but I guess he would paint his models white in order to ... You couldn't tell in the silkscreen paintings that the people were painted white.

You could only tell him these Polaroid pictures. And he did that because he's of course really interested in the aura of glamor. So of course the white paint would remove any imperfections. Warhol was really interested in the cult of celebrity. And it's really interesting to look at these pictures of this unidentified woman, kind of in the context of most of his other Polaroids who are of famous people.

So it's impossible for me to look at these and not think, "Oh, I see these pictures of this woman as she's longing to be famous, longing to have like her 15 minutes of fame." Also, when we were looking at the pictures earlier, there's a lot of interesting things that are happening.

When you see the group of photographs together. I guess in my own practice, I'm always thinking about photography has this like endless bag of tricks. And as a photographer, you make so many decisions on the way that you can really manipulate the viewer to be totally honest. And one of those decisions is editing. And so when you have this broader scope of 20 photographs, and when he would go into these sessions, he was taking up to 200 pictures of the same person, but what can be revealed through multiple images I think is really interesting.

And then in these pictures, you can really see the flaws. When you can see this little peep on her chest, where you can see her her real flesh versus like the painted flesh. That's one thing that always gets me in photographs are these little details that seem to, I don't know, reveal so much about the image making process.

Karen Irvine:

Yeah. And your work is a lot about the aura of glamor. And in a way you might say that your pictures, who, again, depict your family members kind of in electric colors and interesting poses where you can't always see kind of the full body or the full relationship between two bodies, but that also really expose some of the details of aging. Wrinkles or lipstick that's kind of sloppily applied. So in a way, what I think your work has in common with the Warhol Polaroids is that it's almost like a perverse glamorous shot, if you will.

Natalie Krick:

I love that. That's so much more interesting than flawlessness. And actually I wanted to talk about how I learned about posing. Lisa, when I was in grad school, Lisa had just graduated. And at that point I was just kind of having people pose for the camera themselves, I wasn't really directing them. And Lisa totally taught me the trick of going through fashion magazines and picking out poses and having your subject perform those poses. And it was such a huge influence.

Karen Irvine:

That's cool. That's cool. That's a great story. [inaudible 00:16:07] Awesome.

Lisa Lindvay:

I was an anonymous woman once.

Karen Irvine:

You were both talking in the vault about having had glamour shots made at the mall when you were young. That was kind of an amusing story.

Lisa Lindvay:

Yeah, I think it's like one of the things that's so appealing about the Andy Warhol pieces, but even thinking about Natalie's work and my own and where we overlap is everything we understand about ourselves is mediated through culture and magazines and beauty ideals.

And so just thinking back of these fake photographs that you often get taken of yourself and when I was in fifth or sixth grade, I got glamour shots and Natalie was ...

Natalie Krick:

I think I was just going into seventh grade when I got mine. So a wee bit older.

Lisa Lindvay:

We'd go to the mall in our normal clothes and then go to this boutique that dolls you all up and does your hair all crazy. And then you get to be this different persona, which is actually really weird to be a seventh grade girl feeling like she needs to go to the mall and look like Marilyn Monroe or just these really sexualized ideals of what being feminine is.

Natalie Krick:

But also there's such a disconnect there too, because it's something that's seen as sexual, but I don't know. When you're also when you're a kid or even when you're an adult and you're wearing lipstick or whatever, it's not necessarily sexual.

Lisa Lindvay:

[crosstalk 00:17:44].

Natalie Krick:

No, it's a facade.

Lisa Lindvay:

Yeah.

Natalie Krick:

Which is why it can be fun.

Lisa Lindvay:

It can be fun [crosstalk 00:17:50].

Natalie Krick:

[crosstalk 00:17:51]

Lisa Lindvay:

And wearing a feather boa every now and then is great.

Karen Irvine:

Well, I think it's so interesting that idea, the pressure on women, if you will kind of does feed into both of your works, but in really different ways. I mean, Natalie is talking about the kind of the pressure to be glamorous and attractive, but even in your work, Lisa, there's also the pressure on women to let's say, raise the ideal family and be this perfect homemaker. And so you're both kind of coming at feminine identity I think from two different poles actually, which really compliment each other nicely.

Lisa Lindvay:

Yeah. I think I was raised by a male and I have two younger brothers and my mother has always dealt with mental health issues. And I think really just starting to think about too women's issues are also men's issues. And I think oftentimes we kind of forget the things that men are doing and going through too. So for me, it was a lot about taking the men in my life and starting to pose them based on fashion magazines and art history in these things that are like typically female in nature.

And so even starting to change that conversation and think about that or just the absurdity of gendering bodies and ways based on what they wear, how they look. So for me, it started to be a lot more to just about gender roles and how those exist within my home and also exist outside of just we always talk about the things that are female or look at the female body, but also how those things can follow male bodies too.

Natalie Krick:

Yeah. I can't help but think about the photographs of your dad. And sometimes his belly almost seems like a very womanly, pregnant body and how at this time he actually, I mean, he became this caretaker. The mother figure it really for your family and how you can depict that through pose and through the body.

Lisa Lindvay:

Well, and I think the other thing that's really thinking about the overlap in our work too is the fact that both of our families have kind of allowed us to step into these spaces and be really vulnerable. And we do these really crazy things to them sometimes or at least sometimes I put my brother in a pose and he's like, "What are you doing to me?"

And I think there's that performative nature and that collaborative spirit that is one of the things I've always admired about your work and also the fact that they're okay with like not being so beautiful or what we stereotypically think of as beautiful. And that's scary to be that vulnerable in a picture.

Natalie Krick:

Definitely.

Karen Irvine:

No, that's great. And yeah that idea of the personal becoming political. Are there other instances in both of your projects that ... Or what is your kind of ultimate agenda, would you say with the work? Is it possible to summarize that in a few sentences?

Natalie Krick:

Oh, I feel like I can only make work about my experience and I think I'm thinking about gender in a way that I think a lot of people are questioning gender right now. And I mean, I do think that there's definitely something political about that. And that's something I've always wanted to question is this performance and how photography contributes to that too. Really how we learn gendered ways of presenting ourselves through our family, but also through images.

Lisa Lindvay:

Yeah. I think when I started this project a long time ago, I think there was a little hesitation because I think there is a kind of a cultural fear of talking about mental health. And for me, my whole life, you're told, "Don't do this, don't do that. Don't talk about these things. These aren't things that we talk about."

So for me, I think there is a rise in just mental illness and the kind of working with young people in my everyday life. I'm seeing that as a really, really important factor that we often just negate and don't want to talk about. So for me, it's been really, really rewarding to talk about mental health and to show it in a way that's not what we're used to seeing. It's not the thing that we see on TV where people are wrapped in coats and put in rooms.

And so to talk about the fact that everyday people deal with mental health issues and that those have lasting effects on the people around them and the spaces that they live in. And also that you can be beautiful and happy and still also be sad and have these deeper things that exist too.

Karen Irvine:

So Natalie, you were talking earlier about what's revealed through multiple images and both of you have been working for a really long time on your projects and your themes. Can you talk a little bit about what's revealed due to the long-term nature of the investigation? And I was thinking earlier specifically about aging. In Lisa's case, we watch your siblings and your father age in front of the camera. And of course Natalie's work has a lot to do about the aging body and so forth.

Natalie Krick:

I kind of like using multiple images to confuse the viewer. Because in my case, my work really isn't about my family, even though I use them. And I guess in a sense it is about them a little bit, but it's so performative and directed by me. But I mean, I definitely like the fact that you can see a change in appearance in my sister and my mom, but I really was trying to, over the years that I was making that work, I was trying to confuse my mom's identity.

I wanted the viewer to see all of these pictures of the same woman, but think that perhaps it was different women. And then I started to use myself and my sister as well. And it's interesting because a lot of people will look at the pictures and they don't know who is who.

And I think that's photography is so powerful because of the editing process. And even with the pictures, the Warhol pictures that we were looking at earlier, we were talking about how there was so much fluidity in the way that this woman looked just because her of her pose, just these really slight changes in pose. She did look masculine in some and feminine in others. And once you are editing down a photo shoot, you really lose that. So I guess I'm thinking about the long-term project and multiple pictures to really confuse the viewer.

Lisa Lindvay:

Yeah. And when I started this project, I just had started grad school. So I think I was 23, 24. So I was really young and I felt really lost coming to grad school because you get uplifted, you have this idea of what you're going to be or what you're going to do. And then I landed here in Chicago and was like, "I have no idea who I am or what I'm going to be."

And these things just started to happen at home. It was my first time away from home. And so I just started to go back and create photographs and have a deep investment in wanting to be here and to be an artist. And wasn't really sure what that looked like, but knew I needed it to be also back at home making photographs.

And so I think when I started this project, first of all, I was young and just really naive to what that was going to look like. And as time kind of progressed in the project, it did turn into this project that became a lot more about time and going back to the same space. I think one of the really beautiful things about photography is that it does allow for multiples.

And so you can photograph one space in 20 different ways. And so for me, it became a really, really important part of the project was going back to that same space and really starting to see it evolve or devolve in some way and really became a kind of frozen moment of that time. And so the other thing that starts to happen, interestingly enough in my work too, is my brothers look very similar. And so does my sister in some ways.

And so I think as family members, you know you look alike, but you don't think about it too much or you're always trying to not look like family or be your family. But I think even like my brothers and sisters start to get confused in the images as well.

Natalie Krick:

I could not tell them apart. And I live with some of those pictures in my apartment.

Lisa Lindvay:

And that's one part that I really love that kind of accidentally starts to happen. And it's also one thing that I really love about your photographs is that a photograph of your mother, your sister and yourself, that you can see the resemblance. And it's hard to tell who's who at some points and even to figure out ages based on the makeuping or the costuming. And so there's something really just interesting too about that shared identity that starts to happen.

Natalie Krick:

Well, I was really interested in the text with the piece that Lisa chose because it revealed so much more than a photograph alone could. And I remember Lisa always talking about her work and making it a point to not really show her mother in the pictures because of this failure of photography. And although photography can capture so much, to capture someone's mental state is a very challenging and impossible thing to do.

Lisa Lindvay:

Yeah. Well, and I remember being in grad school and people would ask me, "Is this a documentary project or are you conceptual?" And I always would be so frustrated and I'm always like, "Can photography live somewhere in the middle?" I think the things that I think we want to talk about are these larger issues that oftentimes don't visualize themselves. And that's why we don't talk about them.

So it's like, how can we use this tool that is so much about capturing the thing itself in front of it to talk about these things that aren't seen? And so for me, I have always been kind of less interested in the backstory and more interested in the single image and how much of a story can you tell in one picture?

And so for me, it's referencing art history, referencing magazines. So pulling from things that we all understand and that feel kind of universal rather than I think traditionally in photography, we're always thinking about what makes things other? And so for me, it's like, no. Actually, what are the things that hold us together? And I think photo does fail at so many things and there's also this interesting thing that happens where we like trust photography and we don't, which I think also comes into play in your own work.

Natalie Krick:

Yeah. I think that's really the most interesting thing about photography is this relationship to fact and fiction. There's always it's simultaneous.

Lisa Lindvay:

Yeah.

Natalie Krick:

And I think as a photographer, it makes a lot of sense to use those visual cues from culture to talk about something broader. And I guess that's one thin talking about photography that I feel frustrated a lot with is I don't really want to talk about the reality of the situation necessarily. I want to talk about the pictures.

Lisa Lindvay:

Yeah. Or you're talking about the reality through the falseness of it. So like thinking about glamour magazines. It's amazing to me that we idolize Kim Kardashians and like these other people who are so clearly and openly talking about how they've had all these things done to them.

And that's something that we believe to be true about how they look and who they are. And I think your photographs are really fighting against that and starting to peel away those layers by actually applying more layers if that makes sense.

Natalie Krick:

I definitely think a lot about layers.

Karen Irvine:

I did want to ask you both about your working process because obviously you're dependent on your models and have to kind of probably schedule time and so forth. But how often are you working kind of in your heads? How obsessed are you with kind of thinking about your work and are you planning it as you walk down the street before you get to, let's say your family's home or set up the time with your family to shoot them? Are you pre-planning photographs or is it more spontaneous than that? I'm just curious to get inside the mind of an artist and how much it kind of consumes your mental space.

Natalie Krick:

I'm consumed. I would say unfortunately, I'm thinking about it all the time and I wish there was space in my brain for other things, but sometimes there's just not. I plan a lot ahead. I plan everything ahead. And I mean, I know Lisa has done this too, collecting a lot of poses from magazines or pictures from the internet to copy. I mean, I think we're both doing a lot of pulling from culture and copying in our own way, but then I'm also thinking about stylizing and lighting and props and I guess a lot goes into each picture that I make of. There's lots of planning.

Lisa Lindvay:

Yeah. And I mean, I think I have more ideas than I ever have time for. And because for the project I have been working on, which has really consumed the last 12 years of my life, that is back in Erie, Pennsylvania. And so I live in Chicago and so that's an eight hour trip and I don't get to go often enough. And so a lot of that is here, I'll think about things or see things on the street and catalog it a lot of research.

And then when I get there, I will try those things and it tends to all fall apart. And so then there is that kind of reacting to the situation because things are never, ever as I plan or anticipate, which is what I think keeps me interested and keeps me going back because that does mean that there's still more to learn from that subject.

Natalie Krick:

Yeah. I think that's a good point. I think it's good to go in with a plan, but it would be so boring if everything went according to plan and that's why photography is so exciting is because there's so much room for being spontaneous and being surprised.

Lisa Lindvay:

Yeah. I tell my students all the time it's not fun if it's not hard.

Natalie Krick:

It's true.

Karen Irvine:

Thanks for listening to Focal Point. Focal Point is presented by the Museum of Contemporary Photography at Columbia College, Chicago in partnership with WCRX. Special thanks to professor Matt Cunningham and student production intern, Wesley Reno. Music by [Xavi 00:33:38]. To see the images we discussed today, please visit mocp.org/focalpoint.

You can also follow the Museum of Contemporary Photography on Facebook and Instagram at MOCPchi. That's M-O-C-P-C-H-I and on Twitter at MOCP_Chicago. If you enjoyed our show, be sure to rate, review and subscribe to the Focal Point anywhere you get your podcasts.

![lindvay[1].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a9ec0255417fc5100d91a01/1561668648937-HW4HMES4KF40OZPA8F9G/lindvay%5B1%5D.jpg)

![krick[1].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a9ec0255417fc5100d91a01/1561668812784-ZO6ULASXSAJ5ND6OQ977/krick%5B1%5D.jpg)