Episode 3: Dawoud Bey and Teju Cole

In this special extended episode, photographer Dawoud Bey and writer, critic, and photographer Teju Cole are in conversation with MoCP’s curator of academic programs and collections, Kristin Taylor. Bey and Cole discuss works in the MoCP’s permanent collection by Roy DeCarava and Melissa Ann Pinney as well as their thoughts on seeing, understanding, and creating images in the world today.

Works discussed in the podcast:

Interview Transcript

Kristin Taylor:

This is Focal Point, the podcast where we discuss the artists themes and processes that define, and sometimes disrupt the world of contemporary photography. I'm Kristin Taylor, Curator of Academic Programs and collections at the Museum of Contemporary Photography at Columbia College, Chicago. Here are our guests Dawoud Bey and Teju Cole. This is Louis Armstrong's version of Go Down Moses, the song for which Teju's exhibitions takes its name.

Dawoud Bey is a widely acclaimed photographer and educator, over the many decades of his career, he has used portraiture to convey the complex anteriority and humanity of individuals. His recent works newly visualized chapters of American history. In the Birmingham project, he interprets the 1963 bombing of the 16th street Baptist church in Birmingham, Alabama. And a new series of landscapes traces the routing of the underground railroad through the Ohio landscape. Teju Cole is an acclaimed writer, photographer and critic, and the former photography critic of the New York Times Magazine. His works across mediums considers themes of humanity, movement, chaos, freedom, hospitality, and hope. He is the guest curator of the Exhibition Go Down Moses on view at the MoCP until September 29th, 2019. This exhibition is a re-interpretation of the museum's collection. It can be understood as a visual tone poem, interweaving the past and present, and suggesting an aesthetic approach to understanding the current psyche.

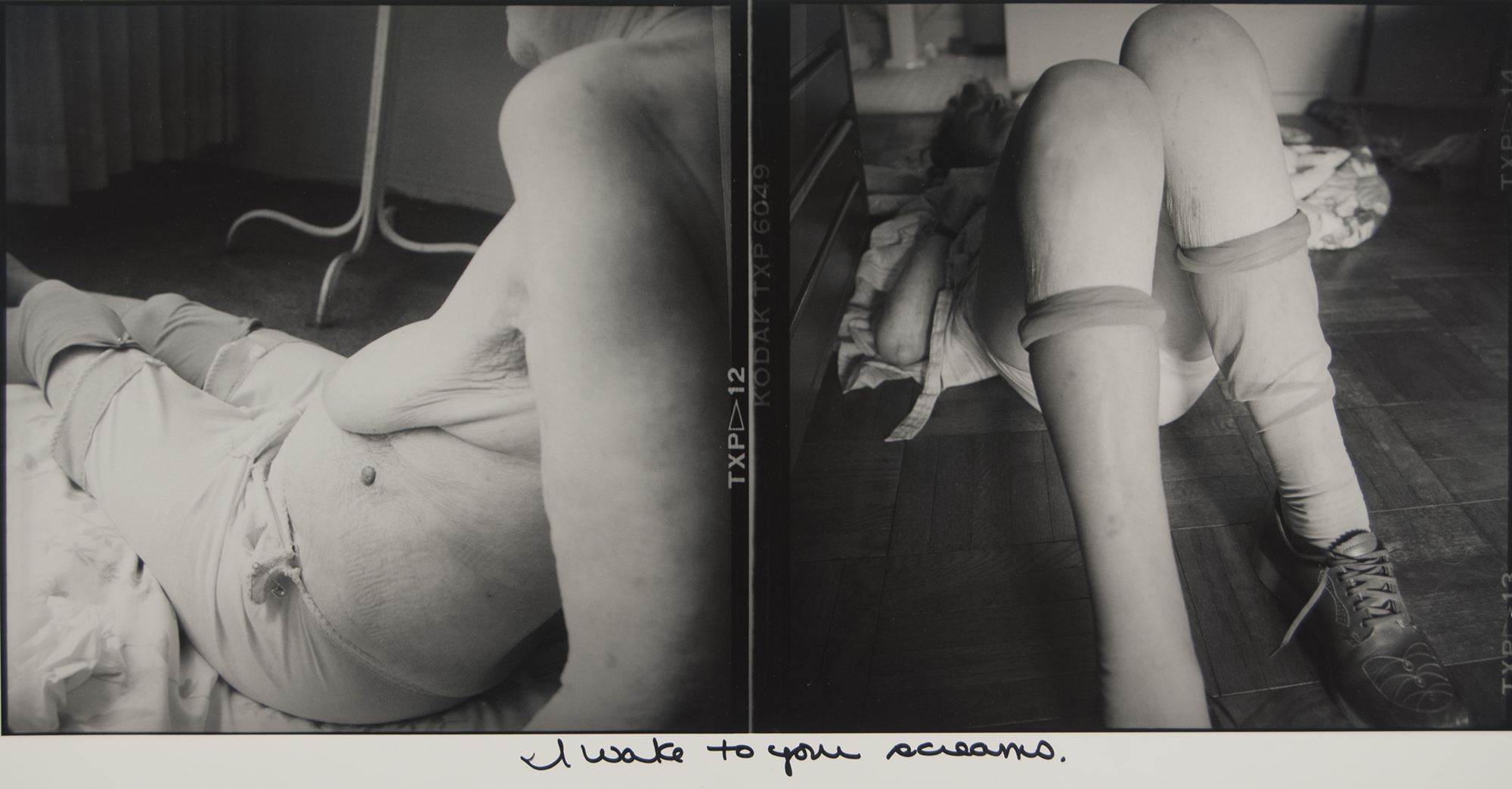

So you're standing in the third floor gallery of the MoCP, and on the wall is a tightly hung cluster of photographs and each image depicts some sort of disaster such as a burning building, or the victim of a car crash strewn across the highway. Beyond these images that are very difficult to look at, is one photograph hung entirely alone, it has a black frame with a black mat and it's on a black wall and the image is so dark that its difficult to see the subject.

Dawoud Bey:

My name is Dawoud Bey, and I'm looking at Roy DeCarava's photograph, A Man and Window which I have looked at quite extensively for a number of years. And Roy DeCarava, the photographer whose work and presence has been meaningful to me almost since I became interested in making photographs and this particular photograph, I think exemplifies a lot of this things that I find meaningful about DeCarava's work. One of this being there, that's an exceedingly ordinary subject that has been elevated to a level of deep observation and interest. And it's a man doing... I guess we could say the most ordinary saying I've always thought that he is kind of buried in the soft light of a television that he's looking at. A man who I happened to know, because I know where the photograph has mattered after he lived across the street from DeCarava's house in Brooklyn. So probably someone that he had had time to observe, to think about how he [inaudible 00:03:38], framed the experience of this long black man.

Kristin Taylor:

We then head down to a gallery on the museum's first floor where we see photographs of people lying down and resting.

Teju Cole:

My name is Teju Cole, and I'm here at the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago. We're looking at a picture by Melissa Ann Pinny, a Chicago based photographer. And the photograph we're looking at is called Cannella School of Hair Design. Melissa Ann Pinny's work was new to me, when I began to curate this exhibition. And she was one of many photographers whose work I discovered in the archives of the MoCP. I have two pictures by her, in this show. And what I found very striking about her work was not nestle, just its subject. The series is very much about Chicago, but about certain moments that she captures that are very quiet thoughtful and somewhat so real moments that are actually showing perfectly ordinary things.

This picture about the Cannella School of Hair Design is a color photograph of an interior space of a young woman with her head in... resting on a sink and a hairdresser's sink. The hairdresser is nowhere to be found. So it perhaps makes you think this is a moment in the process of getting your hair done, maybe a perm or something where something has to be washed out or allowed to rest for a moment. That's what the picture is technically about, but what we see is somebody's leaning back in a chair with some kind of gray apron on her and her had thrown back, and it's a very vulnerable, soft, interesting pictures. It provokes our sympathy in an unexpected way.

Kristin Taylor:

Welcome, and thank you both for being here. It's an honor to sit with you right now. I want to start with you Dawoud, you knew instantly which artists you wanted to talk about, and you talked a little bit about DeCarava's influence on your work. Can you talk a little bit about his specific influence on the work you're making more recently of landscape work that you exhibited at the Art Institute earlier this year?

Dawoud Bey:

Well, DeCarava is certainly an early influence in terms of the affirming for me that there was such a thing as a black photographer. It made that nation idea kind of tangible and my more recent project Night Coming Tenderly Black references, and I guess pays tribute to DeCarava's work in very a direct way that work has a series of photographs printed to appear as nighttime landscapes that references the reimagine path of fugitive slaves moving through the Northeastern higher landscape. And when I thought about the work initially, the black subject and the photograph objects and the photograph being a bad to blackness, I've taken the blackness as the subject, the blackness of the narrative and the blackness of the photograph or print brings me face to face with Roy DeCarava. His work to me embodies all of those ideas.

Kristin Taylor:

And Teju, DeCarava is very important to you also in the exhibition, and you wanted to choose him, but Dawoud had already taken it. And in the exhibition, you've in conversation called it, The Grace Note to the exhibition. It's sort of the last picture you would see if you were moving sequentially through the exhibition. And can you talk a little bit about why you consider it The Grace Note, what that means to you?

Teju Cole:

Yes. When you're putting together a show, you're thinking about images that do a certain kind of work when they're put next to each other, next to other images. The criterion for a photograph being in an exhibition is not, can it hold a wall by itself? But what kind of work does it do echoing, amplifying making meaning through its juxtaposition with others, nevertheless, you end up with certain images that really can hold a wall by themselves that are powerful in themselves. So all the reasons that Dawoud just mentioned, but this kind of analogical union of many different senses of black that we see in several photographs by Roy DeCarava made his 1978 photograph man in a window, sort of the perfect way to end this exhibition. Very clearly when you move through the space of the museum, you come into a room where there's a lot of photographs on one wall, and then over there at the end on another wall is one single image that calls to you and says, come look at this and think about this as a final note in the exhibition.

As a writer, I often think about how do we end things, what is an ending? And I don't believe an ending has to be loud. I think an ending very often can bring us into a contemplative space through which we can understand what has gone on before. So I believe that DeCarava is one of those artists that helps us understand that politics, political thinking, libertory thinking does not have to be loud. I happen to think that Dawoud Base another of those artists. And when I saw night coming tenderly black, it affirmed and confirmed for me actually, the way that his thinking is cognate with the kind of thinking that DeCarava did throughout his career. So I was very moved by that exhibition and it was very glad to be able to see it.

Kristin Taylor:

Yeah. So let's talk about curating a little bit because in the exhibition Night Coming Tenderly Black, Dawoud you also pulled work from the Art Institute of Chicago's Permanent Collection and put together a companion exhibition outside of the walls of your own work. How, and you've curated a little bit before I know that you talked about this earlier, the Wadsworth and the Weatherspoon Art Museum, and even at the MoCP, I understand. Can you talk a little bit about how that process, maybe differs or is similar to the rest of the work you do in making photographs and Teju the same question for you, because I know this is your first major curatorial project. So both of you can talk about how that process is similar or different to the other work you do.

Dawoud Bey:

I think for both of us, who both make photographs and we think about extensively the idea about the photograph in the museum collection is a very fertile space for thinking. Space for realizing that each photograph, which may have come into a museum collection, can be in fact, reshaped into multiple narratives. And I think the artist we give ourselves the freedom to think about museum collection perhaps in a way that's a little more liberated and on more than conventional curator thinking about perhaps bringing those books into your collection to fill certain gaps in the collection. They're looking at that within the context of a very specific set of works that they already have, and then along comes someone who's not beholding to any of that who might be thinking about something else entirely. Which in fact, the work in the collection can also support and [inaudible 00:13:25].

So for me with my work, because the Night Coming Tenderly Black photographs to fundamentally landscapes, I wanted to start by looking at the way in which the American landscape has come to the visualized and photograph going back to the 19th century surveyed photograph, which is the first encounter between the landscape and photography. And then moving forward to look at the way increasingly that the black subject came to inhabit both the American physical and social landscape, and the way that, that relationship had been visualized in photography and photograph. And it was important to me, also because while there are no nominal or little black figures or subjects in that work. That work is very much meant to be seen as if through the eyes of the unseen black subject.

And so curating the powered on exhibition from the yard Institute collection allows me to bring the black subject physically into the conversation and to amplify some of the ideas that inherit in my own project. And it was just a way for me to think about this idea of the black subject and the American landscape, not to again, making photograph, but going through your collection and shaping a different conversation through that collection around my set of concerns at that particular moment.

Teju Cole:

Yeah. A lot of that definitely resonates the possibility of an individual coming in and making the collection do something that it did not know it even had in itself, but possibilities that were latent. I think an archive might have been made for a particular set of reasons. But our archive is a material deposit that now becomes collective property and becomes open to new readings as institutions evolve and become more expansive and more inclusive in their thinking and their possibilities. The archive remains this perpetually open field in which various of the things could happen. And I think that's why it is important to bring in people who are not necessarily experts to help rethink the archive because the archive is common property that has potential. The immensely privileged work that we do as artists and thinkers about art, is not a one-track work.

It is multifarious. When I make photographs, I'm thinking about photography through the camera in my hand, and my editing of images and making of books. When I write photography criticism I'm thinking about photographs through writing about other people's work or looking at their work, going to exhibitions, studio visits, and writing about their work. When I write about my own photographs, for my own books I'm doing that, but in a different kind of way, because now I'm thinking about my embodiment and what it means for me to be in a country and take photographs there. And these are all sort of continuous activities that are distinct, but they have significant overlap. So that when I step into a place like this, and I do an exhibition, it's a continuation of this privileged, but important set of practices, thinking about photography.

I think about photography with my hands and with my eyes and with my body and with my presence. And with the way I organize photographic experiences for other people. Being invited to give a lecture is another practice. And they are all related in very, very interesting ways. So they keep sort of feeding each other. So I definitely enter a space like this, not as an expert but hopefully not naive either, because I've spent the better part of the last decade, just really thinking about photographs and being exposed to them every day. So there was a kind of a readiness there as well.

Kristin Taylor:

So when our Director, Deputy Director and Chief Curator, Karen Irvin asked you in the interview for the publication for Go Down Moses, what our archive was missing, you said the vernacular photographs are just kind of the everyday pictures that people are taking all the time. And Dawoud, I noticed in your exhibition, you curated at the Art Institute, you put some of these everyday photographs of vernacular photographs. Can you both talk a little bit about the importance of that kind of photography to you? And a bigger question is where you see photography heading at large since it's changing so dramatically every day? Big question.

Dawoud Bey:

Well, I think for me as I was going through the Art Institute Collection, they had recently acquired a large number of what you would call a vernacular photographs. [inaudible 00:19:32] we will never know. And as I started going through those vernacular photographs, I was in this particular context, very much interested in those pictures that contained black subjects, because I began to think about it. I was shaping the exhibition. I wanted to do a shift and include photographs that suggested not only the black subject was pictured and photographs made by others, but how in fact? The black subject, has engaged in the act of what you might call [inaudible 00:20:22], how they have visualized their own set of social circumstances by photographing their friends, their wives, their lovers whoever, and a very casual but I think meaningful way this question by making one's presence visible through a photograph, which of course was never intended to end up in a museum exhibition, but what at the very least made it as an act of self affirmation and affirmation of one's presence in the world, a kind of visible affirmation of that.

And so within that particular curated exhibition, I wanted to include these photographs as a way of amplifying the way enrich black people have seen and pictured themselves and the social landscape of their own world.

Teju Cole:

I'm intrigued by what Dawoud describes as a self authorship there, because I think it's such a crucial part of recovering the past. Probably for all of us when we're growing up history is a very clear... has a very clear idea of what it thinks it is. Histories, the deeds of great men, some women. Great white men made certain decisions that turned the course of certain things. And then you sprinkle a few token others in there. Some black people, some Asian people, some women, some queer people, but really history is the great deeds of great people. There's been, out of revolution in historical studies has not necessarily caught up with popular audiences yet.

We're still very interested in the acts of great men, but the understanding of historical studies now is that it is really worth it, trying to retrieve the activities of ordinary people everyday life, the history of everyday life as with so many things, the [inaudible 00:22:42] have tried to take credit for this, the [inaudible 00:22:45] school but cultures all over the world have actually understood that, the way that ordinary people think and the actions that they take and the decisions that they make are what constitutes the history of a nation and of a people that's where custom comes from, that's where tradition comes from.

The history of photography must be the history of everyday life as well. Icons are fine, Photographic icons are fine, and Iconic photographers are also fine. Great photographers, people who dedicated their lives to it, very often can hit the mark in a way that's intriguing and very moving, but it is also true that each great photographers narrowly in their own lane and to stop bringing in material that is made by people who are not credentialed or pre-certified as experts, professionals or great, allows us access to all kinds of submerged and ignored histories, because if you only took submerge, if you only took major or great photographers for the first a hundred years of photography's history, let's say between 1830, 1826 and 1926, well then you're just going to have white people or black people as seen by white people.

But if you start allowing other voices to come in and you start and you start asking questions such as, "Well, what was photography like in West Africa in 1890 or in East Africa in 1910 or in Alabama or in Mississippi, or in Harlem?" Who is doing the work? Who's working? Had the fortune to survive? It doesn't mean you necessarily bring all the artists back as great artists, but it means that you question the whole enterprise of greatness and say, "How do we reimagine the past?" And so I, and even for the contemporary, I very much believe in these informal and quite energetic channels that give us a vision quite different from what somebody who has an MFA can give us.

Kristin Taylor:

So we should probably talk about your collection choice now, because we haven't really talked about Melissa Penny's work too much. Why is her work such a standout? Is it a little bit of what you were talking about of that everyday moment that she captured in the beauty salon? Or is it something bigger about this other force of punctum that was guiding you? Can you talk a little bit about the idea of punctum and why Melissa Penny?

Teju Cole:

Yeah, that's interesting, I mean, you said, is it something bigger, such as punctum, which I actually think of as something smaller, there can be an energy in certain photographs and that has been a bit of a guiding principle for this exhibition as a whole. The exhibition has maybe 150 images in it. For sure many of them are content driven. Many of them are driven by visual analogy and resonance and forms of repetition in building a visual argument. But many pictures are in the show because there's something in them that does prick that stings that calls out to you. This is the mystery in [inaudible 00:26:41] photography, that it is simply what the camera has pointed at, but it is what the camera in spite of itself, and in spite of the image maker has discovered, what has been caught on the fly by the image and has remained permanently at rest inside that image.

If we look at the Gordon Park's photo early photograph for him, of the boy on crutches, it's there in that picture. What I describe as a sort of gentle surrealism, but I'm always looking for this moment, that's a combination of the tender and the unexpected, where then there's some kind of tension in your interpretation of what you're you're seeing. Because I think if we're talking about the intensities of a present moment, I think tenderness combined with strangeness is one of the ways we can access that, like on a very intimate level. So that's something I see in Penny's work. And I do have to say that, all photographers it's not as if, she's got hundreds of pictures like this it's that she's got a fine body of work, and then certain pictures just hit you right between the eyes.

Very few people are Robert Frank, who hit that mark again and again, and again, and again, Roy DeCarava hit that mark so many times, if you take a volume of his, of his work. Every other picture, you just hold your head and say, "Oh my God! How?" most photographers cannot do that. But I think, for a photographer even in a lifetime to have, a dozen pictures that really hit that mark, I consider that as sort of a great success.

Kristin Taylor:

So you, at the end of the exhibition have a lot of images of that are hard to look at of violence and chaos and destruction, and Dawoud, I've heard you talk about how you started the Birmingham series. The project was started from an image that you saw that was very difficult for you to look at as a child. Can you describe that inspiration for you in that image and the importance of that image to you?

Dawoud Bey:

Well, the image that you are referring to is a photograph of a shared with Jane Collins, who was the sister of one of the four girls who was killed in the diameter of the 16th street Baptist church in 1963. And encountered that photograph when I was, I think about 11 years old, and everything changed for me. Seeing that photograph. I've always thought of a day of my life before that photograph and my life after that photograph. And it was a photograph of her laying wounded in a hospital bed with big [inaudible 00:30:15] bandages over her eyes. And I don't know that I intuited at that moment that one of the reasons that it was having such a profound effect on me was that I was very near to being the same age as the girl in the photograph. I think I might've intuited it without actually knowing it.

And that stayed with me for a very long time until several decades later as an adult more than fully grown adult, I actually awoke with a start one morning, and that image came flashing back to me. And I decided I needed to do something with that. I needed to make something out of that I knew to respond to that by making something. And that began a series of several visits to Birmingham, Alabama, over several years, becoming familiar with the place and also thinking all that time. What do you make in response to something like that? It happened it's in the past, did not much to be seen, No. Although, in some way there is, it seems to starred those kinds of traumas kind of linger in the atmosphere and the [inaudible 00:31:57], but in the most fundamental sense, there's nothing to see I said, "How does one make more about that?"

And I finally came to this idea making photographs of young black girls who were the ages of those four girls in order to give those girls a palpable, physical presence. To make photographs of young African-American girls? No. Who are the ages that they were in order to give them a less mythic and more tangible, physical presence. And as I thought about it further wanted to figure out how to nonvisualized the passage of time. How you do the thing with a camera that photography is designed not to do. It's designed to make a still image of a moment. How do you make something about an extended period of time? And that's what I came to the idea of making photograph of women were now the ages that those young girls would have been. And empowering them, I could actually make a [inaudible 00:33:16] that did in fact, embody 50 years [inaudible 00:33:20] to figure out how to embody individualize the idea of time in the still photograph in a way that resonated very deeply, not other documentation because it isn't a documentation.

It's not them, but it is done in a deepest sense. So those girls and women, and there were two African-American boys killed that day. So I did the same thing, photograph from boys who were their ages of the two boys and men who are the ages that there was would have been, really made me begin to think about the possible ways to enrich the photograph, could actually be [inaudible 00:34:11], which one might talk about and in some way, visualize the past in the contemporary moment. And that pretty much set the trajectory for the work that I've continued to do to make photography, which is of course, when it's made, it's made in the now, but how to make it resonate in a very palpable way with a sense of history.

Kristin Taylor:

Let's bring it back to your exhibition a little bit. You actually included one of Dawoud's photographs in the exhibition and it's more street photography type image photographed in New York. It is called Third Street Basketball Court, New York city. And it was taken in 1986, but you've also written about Dawuod's work before in the New York Times in an article called There's Less To Portraits That Meet The Eye and more. Is there a particular project that Dawuod has made that is your favorite or what, what work do you appreciate by him the most? And the same question for you Dawoud about Teju, Is there something that he's written that resonates with you the most?

Teju Cole:

When I answer the question for him. He likes the essay I wrote about his work on a purely neutral basis. Of course. Well of course Dawoud is one of our leading photographers. So one sort of looks at that body of work and it's simply, grateful for it. And when I sat down to write that essay, which was about portraiture, I wasn't saying, "Oh, I'm going to write an essay about Dawoud's work." It's just that I was looking for work that had the amplitude, that allowed me to actually attempt to say something new about what's happening in photographs. And in that essay, I wanted to go a little bit against the grain of the way people normally read portraits, which is you look, read the portrait and you read it physiognomically and "Oh, this person has this sort of eyes and therefore this is their character." Or something like this.

And then just sort of bring it more back to the fact of a portrait as a testimony, to an encounter and a testimony to the artist's sensitivity, very subtle sensitivity, and be a portrait as a place where soft, small, unexpected things can happen that don't have to do with the genetics, but have to do with those little shifts of perception that a really great artists can bring to bear. So that's why I selected that. But to zoom back out of that for a moment. I think, what draws me about David's work is that, he's a good and faithful servant of the given he's functioning in a certain moment in history. There are certain political realities that impinge on the making of the art, is a very serious commitment to the art, that comes both out of sensibility and out of technical skill.

And he's a teacher so you can sort of abstract individual images out, but if you go through the whole sequence of seeing deeply, what you see is a testimony sort of commitment. I do very much like the photographs of the students in the boarding school. Is it boarding school? Students of all races who are in this sort of in-between age puberty, young teens and such compassion for these young people in these very beautiful, large formal portraits. So yeah and as far as the third street basketball thing, so many things just suddenly happened with that picture. One is that it's not, it's not portraiture and there's a sort of angularity and subtlety to it, a touch of DeCarava in that as well, even though, it's obviously very contemporary.

I've been by those basketball courts, numerous times stood their and watch games going way back to 1995. I mean, it's like, it's just, you get off of West fourth, it's right there. It's part of New York there're dudes on there where you're thinking this guy should be in the NBA and then you're like, well, maybe not, because he's like five foot seven, but he sure can play basketball. So there's that, there's a touch of [inaudible 00:39:23] with a chain link and that complexity of that. So it's in conversation with the history of art as well. And I think ultimately if you're also doing this sort of mixed practice of being a photographer, writer, curator, I think there's always also an element of when you select something, there's always an element of that's a photo I wish I had taken. Sometimes it just comes right down to that.

Sometimes you do a show just full of photos. You wish you'd taken, which is a layer of this exhibition. I have not even talked about much, but half the pictures in there. If I look at Carrie Coppins picture it that's in the show of a group of young black men dancing in Chicago. I think my first, my rawest response to it is wish I took that. But this is not envy at all, It's more appreciation, I'm glad it's in the world. I wish I took it. I wish I owned it. I want to be closer to it a little bit longer. I'm going to put it in my show.

Dawoud Bey:

Thank you Teju, to hear you talk about it because that that basketball court is a very iconic location and social space in New York. For those who know and I've been out of New York for a few years now, more than a few years, but at the moment that I made that photograph, I like a lot of people had spent hours standing there watching some of the most extraordinary, most organized and pickup basketball games. And that photograph is really... it's mediocre, and of course all photographed about the photographer looking, but in that particular space, it echoes so much a piece what was very much a seamless part of the fabric of my life, because it's right by the subway station. You can't come and go from the village without passing by that basketball court.

And it's also interesting for me to see the photograph in this exhibition, because that is a piece and a period of my work that is not much shown or seen. So I was kind of surprised to see it myself because I don't see that piece of my work on the wall too often. But for those who know that location kind of like in the way that 57th street and fifth Avenue, you think about all the photographs that [crosstalk 00:42:30] with all of them, that there are certain iconic locations within the city of New York

Teju Cole:

And New York is a little by the corners, right? It's like the corner of this and that, and pick your corner is basic.

Dawoud Bey:

Yeah, And that's one of them. And so, I was just pleasantly surprised to hear it included, because it's also a very it's a very public social moment, but it's also very quietly intimate moment.

Teju Cole:

Oh yeah, but what's on that block is the Blue Note Jazz club. So I mean, think of that juxtaposition, I mean, that photo is jazz, it's not going to coincide... I mean, it's a very mixed spaces, diverse space, but it's not coincidental that what we largely see there are black bodies arms, the figures that are across the picture plane and, you blink and suddenly you're at the Blue Note and Miles Davis is playing there. So there's a continuity to these things because I think locations retain the ghost of the things that happen there, in those locations.

Kristin Taylor:

I'm glad you brought up the Jazz club because music has been also a big influence on this exhibition, down to the title being called, Go Down Moses, you made a custom playlist on your Spotify account to go with this exhibition, and you're always playing music as you were working in the museum. And we've talked about influences are ready a little bit with DeCarava's work, and I know that you also were inspired by Langston Hughes poetry. That was part of the title of your exhibition at the Art Institute. Can you both talk a little bit about those influences outside of photography with poetry, or music, or painting, and are there any that haven't yet worked their way into your work that we can expect down the road?

Dawoud Bey:

Well, I was a drummer before I was a photographer. So certainly music has been and continues to be a very important piece of my way of being and thinking. Most people probably don't know that Roy DeCavara was also a very good, tenor saxophone player. He always said that he was just a student, but that's an interesting way. And with people you have a high regard and a very deep respect for an art form can practice for 20 or 30 years and still call themselves students. And certainly the relationship between DeCarava's interest in visualizing music and his extensive study of John Coltrane extended to his own practice as a musician too.

And because I did study and play jazz and was initially informed and inspired by jazz drummers like Tony Williams, who was actually meant for creative inspiration of any kind of the world lit up for me when I first heard Tony Williams and I was [inaudible 00:46:00] and I had the good fortune when I was very young to be able to study with Tim Berry, some very good teachers as a drummer starting with, [inaudible 00:46:15] with some people who know the music might know, and Milford Graves, who is considered the father of free jazz drumming. So [crosstalk 00:46:27] go into a situation and improvise.

Because a lot of certainly it's probably more explicit in the period of my street photography work, but one has to just go and improvise and find the form and articulate it. But I think every situation that I go into as an artist and photographer making brick, I never know exactly what I'm going to be confronted with, but because you understand the form, you understand the material, you understand the parameters, and you just improvise this notion of improvisation is kind of a foundation to my thinking and my confidence actually as an artist. And I used to write a lot of fiction and poetry in my younger years, published quite a bit of poetry in different literary journals. So all of that it's very much a part of my formation and I think as an artist and photographer, and I think about the world really in different ways to use the materials that the world offers me in some kind of creative articulation.

Teju Cole:

The first time I saw a live jazz concert was in 1992 having just returned here and from, from Nigeria and it was Jimmy Heath, You know that song CTA? which is the CTA. So that, I mean, he wrote that for Miles Davis. So, I mean, that was like really something that anchored me into this tradition. I ended up really, really loving very deeply. And recently I've been thinking a lot about the difference between practices that are integrative and practices that want to separate the world out into like these distinct strands, that silo things off and integrated practice.

I know how nourishing it is, and how satisfying it can feel to encounter in a piece of music in a photograph, the emanations of music in a menu of the emanations of tradition and improvisation in painting the sense that, the person also has a sense of architecture, or dance, or whatever, but it's really hard to say why there's very healthy integration is present in some places and why in some places it's so hard to break into it. I don't know if it's a difference between indigeneity and colonialism. I don't know if it's a difference between blackness as experience and what thinks of itself as whiteness. I don't know if it's a difference between more socially committed political practices and raw capitalism. I don't know if it's the difference between tradition and modernity, all of those things partially map it, but none completely explains it, because it can integration can erupt into a daily mess.

If we give it a chance. What I do know is that's where our health is, separating everything out, turning everything, sort of professional people siloing themselves off, defending their turf and all of this, but life at its best once to sort of bleed in and like dye color, dyes running into each other. So I know that I am at my truest and best self when everything is in conversation and I don't have to make a declaration of any kind of purity. So I'll say well, I don't believe in God, but also God is against purity. Yeah, If I did believe in God, God would be against any form of purity and isolation, because we're all sort of in this together.

Dawoud Bey:

No, I was thinking in relation to this question about music and other influences and thinking about your use of The Grace Note turn in the exhibition, but truth of course, in fact, the music was [inaudible 00:51:53]. And I think it's that DeCarava man in the window photograph, it serve, the shame function within the construct of the exhibition as it were musically, when you have a phrase. And then at the end of that phrase, that particular statement, the grace note at the end against which the phrase is now weighed the Grace Note, and then they kind of set each other off and the Grace Note allows you to consider that phrase in a very different kind of way. In line of that one last flourish.

Teju Cole:

And very often John Coltrane will do like a triplet where the phrase has been there. [inaudible 00:52:49] at the end, They're almost as if it's just saying I'm signing off, he's just sort of played like some like circular breathing thing that has like a million notes in it. And then there'll always be like this little throwing it out with this three note thing that he does. And it's great to hear that DeCarava played, because I mean, if you could take a picture of home, it would be the one of the man dancing in that darkened hole. For me, it would be the portrait he made of Coltrane and Elvin Jones. You know what I'm saying? What a picture, because that picture is music, what does it mean to solo? You can just see Coltrane in profile almost as if the saxophone continues, his profile very close behind Elvin is on drums, but he's just pure grain, dark grain.

He's just dissolving into this bouquet of the lens, but the picture is so musical, it's so there, inside the music it's full of love, but also expertise. They have deep focus on what they're doing. That's a picture that I would like to sort of live with, because this is a conversation, that between the photographer and the man photograph that, as Toni Morrison has said in a different way, sort of eludes the wide gaze, this has not been presented, "Oh, look at us." This is a conversation of love inside a tradition. So he photographed Coltrane, like no one else ever did.

Dawoud Bey:

Yeah. From inside[inaudible 00:54:45]. And that photograph. Which is another picture that I can, it's always somewhere in my brain, it's the formal embodiment of both the music and the relationship between those two musicians, those two men, but it's absolutely exquisite. Lyricism is also the embodiment of the music, but then there's and Elvin and there's Coltrane, and Elvin is in fact the foundation and then Coltrane is the lyrical.

Teju Cole:

And you could almost imagine a second version of that picture in which Elvin is sharp and Coltrane is blurred, right?, Because that is how jazz works. It's an exchange. It's an interchange somebody's emanating out of this. I mean, this is Fred Martin's idea out of this collective body. The soloist is not a star. The solo is... The band is the star. The soloist comes out of the band, like a solo flare and then is reabsorbed into the band, into the collective. So I can see that sophistication in the way he makes that image.

Dawoud Bey:

That's an exquisite photograph, one of my favorite.

Teju Cole:

Yeah. We got to do a heist and steal it from somebody who has a good print of it. We'll replace it with a photocopy.

Kristin Taylor:

Well, I think we are out of time. Thank you both for coming in. It's been a great conversation. Thank you for listening to Focal Point. Focal Point is presented by the Museum of Contemporary Photography at Columbia College, Chicago in partnership with WCRX FM radio, special thanks to Matt Cunningham and Leslie Reno. To see the images we discussed today, please visit mocp.org/focalpoint. You can also follow the Museum of Contemporary Photography on Facebook and Instagram @mocpchi, that's M O C P C H I, and on Twitter at MOCP_Chicago. If you enjoyed our show, please be sure to rate, review and subscribe to Focal Point anywhere you get your podcasts.